Planetesimal Heating

The frequency of Earth-like planets with enough water to host surface oceans is currently poorly understood, as are the conditions leading to their formation and how they can vary between stellar systems born from the same star-forming region. Classical planet formation theory suggests that planets form from reservoirs of material, the composition and water content of which is determined by whether formation occurs outside the protoplanetary disk snow line or not. In the inner Solar System, this results in the formation of water-poor planetesimals, and eventually the conglomeration of these into water-poor rocky planets. However, recent findings from the fields of geochemistry and cosmochemistry suggest that early planetesimal populations were originally accreted from water-rich material (Schiller et al. 2018; Drazkowska et al. 2023; Perotti et al. 2023; Grant et al. 2023), while the bulk water content of the resultant planets is significantly depleted relative to their parent planetesimals.

This evidence presents two important questions: why did the inner rocky planets not remain water-rich, and – more broadly – how many water-rich planets are there in the galaxy?

N-body simulation of star forming regions

26Al and 60Fe, and other such Short-Lived Radioisotopes (SLRs) have a significant impact on the formation and evolution of planets. In particular, decay heating from these SLRs provide the bulk of energy for heating and desiccation of volatile-rich planetesimals in the early solar system. The source of these SLRs is contested, however.

The solar system has a significantly higher fraction of both 26Al and 60Fe than the surrounding interstellar medium, based on observations in chondritic meteorites (Kita et al., 2013). While potential enrichment mechanisms that occur before star formation such as sequential star formation (Gounelle & Meynet, 2012) have been theorised, as well as mechanisms post-planetary formation such as cosmic ray spallation, these do not match with the estimated initial enrichment levels and homogeneous distribution of isotopes across the solar system. Mechanisms that occur during planet formation appear to be more likely, such as enrichment through stellar winds of massive stars and supernovae.

Over my research I have investigated the efficacy of these post-star-formation methods, such as massive stellar wind and supernovae enrichment, as well as AGB interlopers (Parker & Schoettler, 2023). This was achieved through modelling enrichment through wind blown bubbles in N-body simulations of varying population densities. These simulations were performed using the AMUSE Python framework, with the enrichment model written in Numba optimised Python running concurrently with the N-body and stellar evolution models.

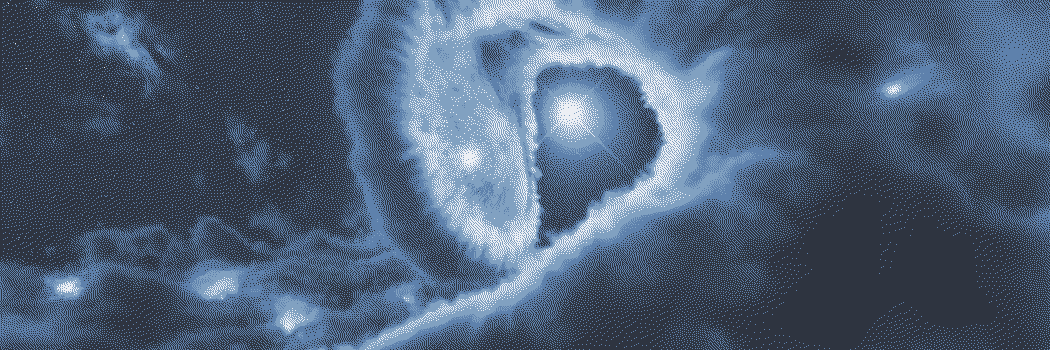

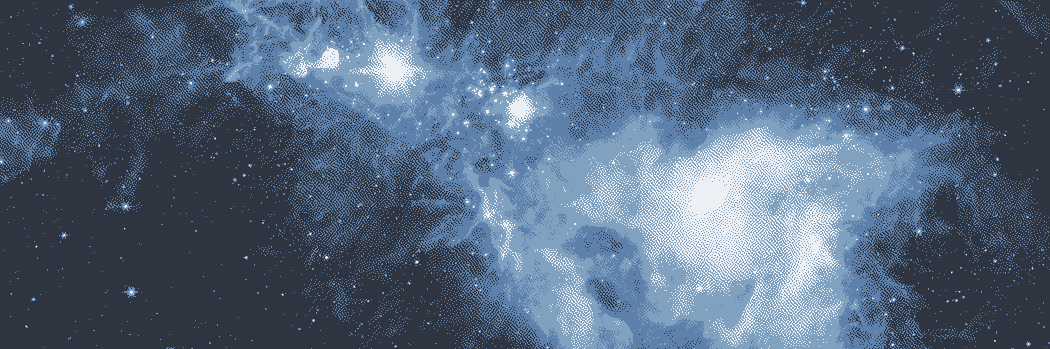

Massive Stellar Winds

Colliding Wind Binary systems are exactly what they say they are on the tin, they are a binary system with winds that collide. Typically consisting of an OB+OB or WR+OB pair, these systems are currently difficult to observe in detail, but also extremely difficult to simulate, for the following reasons:

- There is an extremely large difference in scales within the simulation, the maximum bounding box of the simulation can be on the order of a parsec, while important features are sub-AU in scale.

- The post-shock environment can undergo extremely rapid cooling – from 109 to 104 Kelvin – through plasma cooling in highly metallic flows and dust cooling.

- Accurately simulating outflows and orbits prevents dimensional simplification – all simulations had to be conducted in 3-D.

Despite these difficulties, the study of these systems is extremely fascinating. Despite the extremely violent conditions, from hypersonic shocks to extremely bright EUV & X-Ray emission, there is still a clear production of dust in the post-shock outflow. This is observable as a pronounced infrared excess in the systems spiral-shaped outflow. This dust production can be periodic or continuous, some systems can produce an excess of dust equivalent to an AGB star, while others produce no measurable amount. Some major outlying questions are:

- What is the formation mechanism of dust, and when does initial nucleation occur?

- How are the nascent dust grains protected from their extremely violent surroundings?

Over the course of this project, I implemented a fast advected scalar dust model that ran inside the open-source astrophysical hydrodynamics code Athena++. This dust model is highly extensible and capable of simulating growth, destruction, and cooling of amorphous carbon dust grains within a CWB environment. I hope to extend this work in the future, incorporating more dust evolution mechanisms and refactoring the dust model to behave as its own separate fluid.

Subclustering

Prior to my PhD, I undertook a Master’s project with the aim of producing an automated sub-clustering algorithm for open and globular stellar clusters. This sub-clustering algorithm was written and tested on NGC 2264, an archetypal open cluster.

Another aim of this project was to attempt to map and sub-cluster based on the dynamical motions of stars. This project was undertaken prior to Gaia DR2, and as such, there was insufficient data to accomplish these aims.